Lattice Gas, Hopfield Networks and Transformer Attention

I study a lattice gas in the grand canonical ensemble, a project from my PhD, and show how it connects to transformer models through Hopfield networks.

Introduction

Many physical systems exhibit quite similar collective behavior despite vastly different microscopic details. A gas condensing into a liquid, magnetic domains forming in a ferromagnet, charge carriers clustering in semiconductors, neurons firing in synchrony—all emerge from the same fundamental framework of statistical mechanics.

Consider particles distributed across available sites. At the microscopic level, each unique arrangement is a microstate. For just \(10 \times 10\) sites that can be empty or occupied, there are \(2^{100} \approx 10^{30}\) possible configurations.

Meanwhile, macroscopic measurements (e.g., density, conductivity, magnetization) don’t probe individual microstates. They measure ensemble averages that emerge from collective behavior. The connection from micro- to macrostates is the Boltzmann distribution, which gives the probability of a microstate \(X\) as:

\[\mathbb{P}[X]\propto \exp\left(-\frac{E(X)-\mu N(X)}{k_\mathrm{B}T}\right),\]where we use the grand-canonical ensemble, allowing for the number of particles to change. Here, \(E(X)\) is energy, \(N(X)\) is particle number, \(T\) is temperature, \(\mu\) is chemical potential, and \(k_\mathrm{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant, which we can set to \(k_\mathrm{B}=1\) for convenience.

The probability of observing a macrostate (characterized by a density \(\rho = N/V\)) must account for both the Boltzmann factor as well as the number of ways \(\Omega\) to realize that same density:

\[\mathbb{P}(\text{macrostate}) \propto \Omega \cdot e^{-(E-\mu N)/T} = e^{-\Phi/T}.\]The grand potential \(\Phi = E - TS - \mu N = F - \mu N\) combines energy, entropy (\(S = \ln \Omega\)), and the chemical potential contribution, with \(F = E - TS\) being the Helmholtz free energy. The equilibrium state minimizes \(\Phi\), representing the optimal balance between these competing factors.

The Lattice Gas Model

The lattice gas model provides a minimal framework to study these statistical principles. We consider a lattice of sites, each of which can either be empty or occupied (\(n_i \in \{0, 1\}\)). The key ingredient is the interaction between particles. A classic example from molecular physics is the Lennard-Jones potential, which captures the essential physics of many interatomic and intermolecular interactions: a strong short-range repulsion (particles cannot overlap) combined with a weaker intermediate-range attraction (van der Waals forces). This attractive component is what drives the condensation of gases into liquids and the formation of molecular clusters.

In our lattice gas model, we simplify this complex interaction landscape by focusing on nearest-neighbor sites and capturing the essential attractive character. The Hamiltonian is:

\[H = -J_0 \sum_{\langle i,j \rangle} n_i n_j, \quad J_0 > 0.\]When neighboring sites are both occupied, they lower the energy by \(-J_0\), favoring clustering. This model is mathematically equivalent to the Ising model of magnetism.

Monte Carlo Simulation

To explore the equilibrium behavior, we can use Monte Carlo simulations based on Metropolis-Hastings (GitHub). The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Inputs: temperature T, chemical potential μ, coupling J₀

State: binary lattice n[i] ∈ {0,1}

Repeat for many sweeps (one sweep = L² attempts):

for k = 1 to L²:

i ← uniformly random lattice site

h_i ← number of occupied neighbors of i

ΔN ← 1 - 2·n[i]

ΔE ← -J₀ · ΔN · h_i

ΔH ← ΔE - μ·ΔN

P_acc ← min(1, exp(-ΔH / T))

if rand() < P_acc:

n[i] ← 1 - n[i]This acceptance criterion ensures the simulation samples the correct grand canonical distribution. By running many such steps, the system reaches thermal equilibrium and explores the ensemble of microstates with the proper statistical weights.

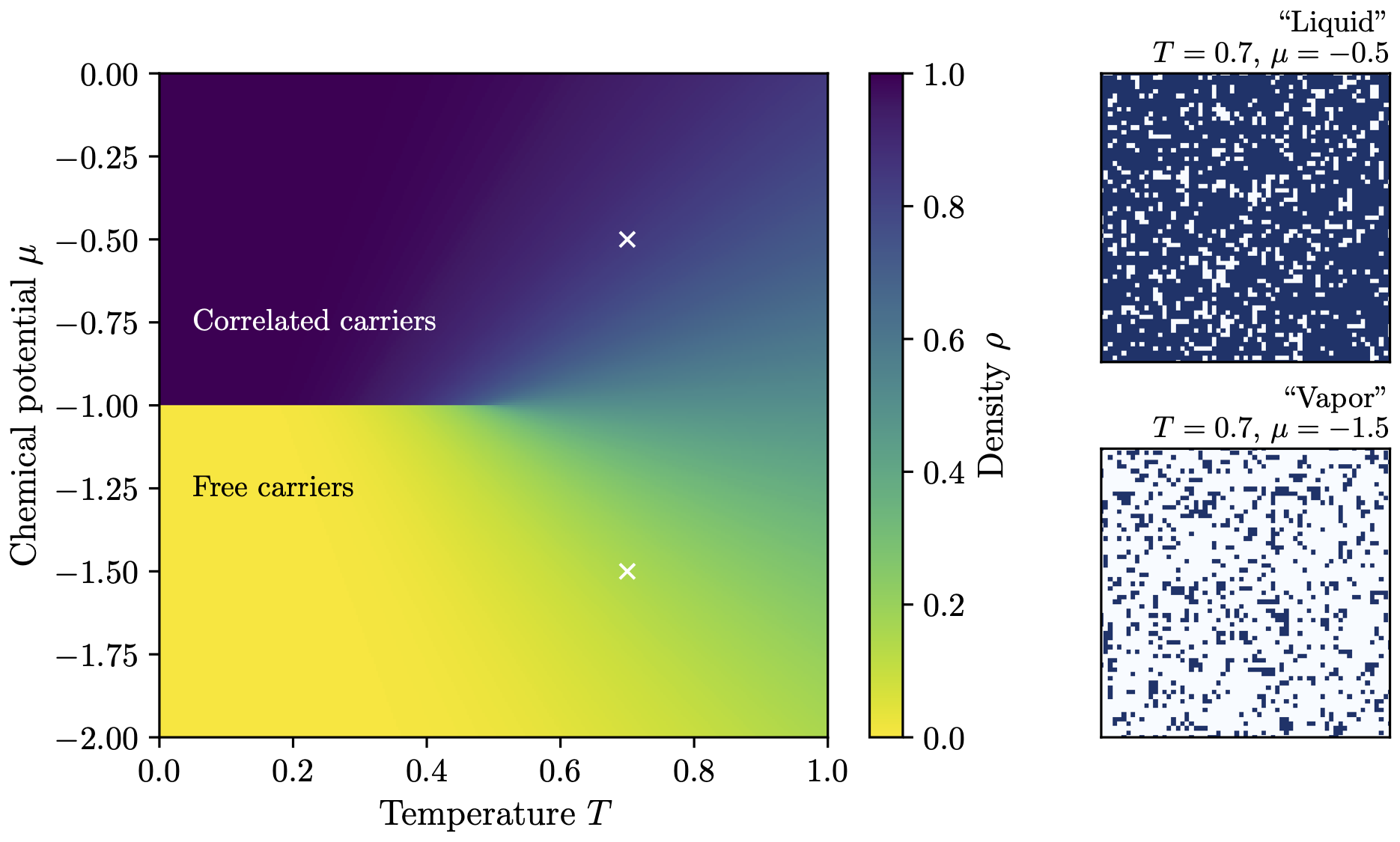

By systematically varying temperature and chemical potential, we can construct the phase diagram shown above. The results reveal two distinct regimes:

High temperature (\(T > T_c\)): The system behaves like a supercritical fluid. As \(\mu\) increases, the density changes smoothly and continuously. Thermal fluctuations are strong enough to prevent long-range order, and particles are relatively uniformly distributed.

Low temperature (\(T < T_c\)): At a critical chemical potential \(\mu_c\), the density jumps discontinuously from a low-density “vapor” phase to a high-density “liquid” phase. This is a first-order phase transition, characterized by phase coexistence and metastability: the system can become trapped in a locally stable state even when another phase is globally favorable.

Mean-Field Analysis

To capture the essential physics independent of lattice geometry, we can use a mean-field approximation where every site effectively interacts with every other site equally, akin to a fully connected network. The effective coupling is $J=\frac{zJ_0}{2}$ (where \(z\) is the coordination number), giving:

\[E(X) = -\frac{J}{V} N(X)^2.\]Accounting for the combinatorial entropy of distributing \(N = \rho V\) particles among \(V\) sites (using Stirling’s approximation), the probability distribution for density \(\rho\) becomes:

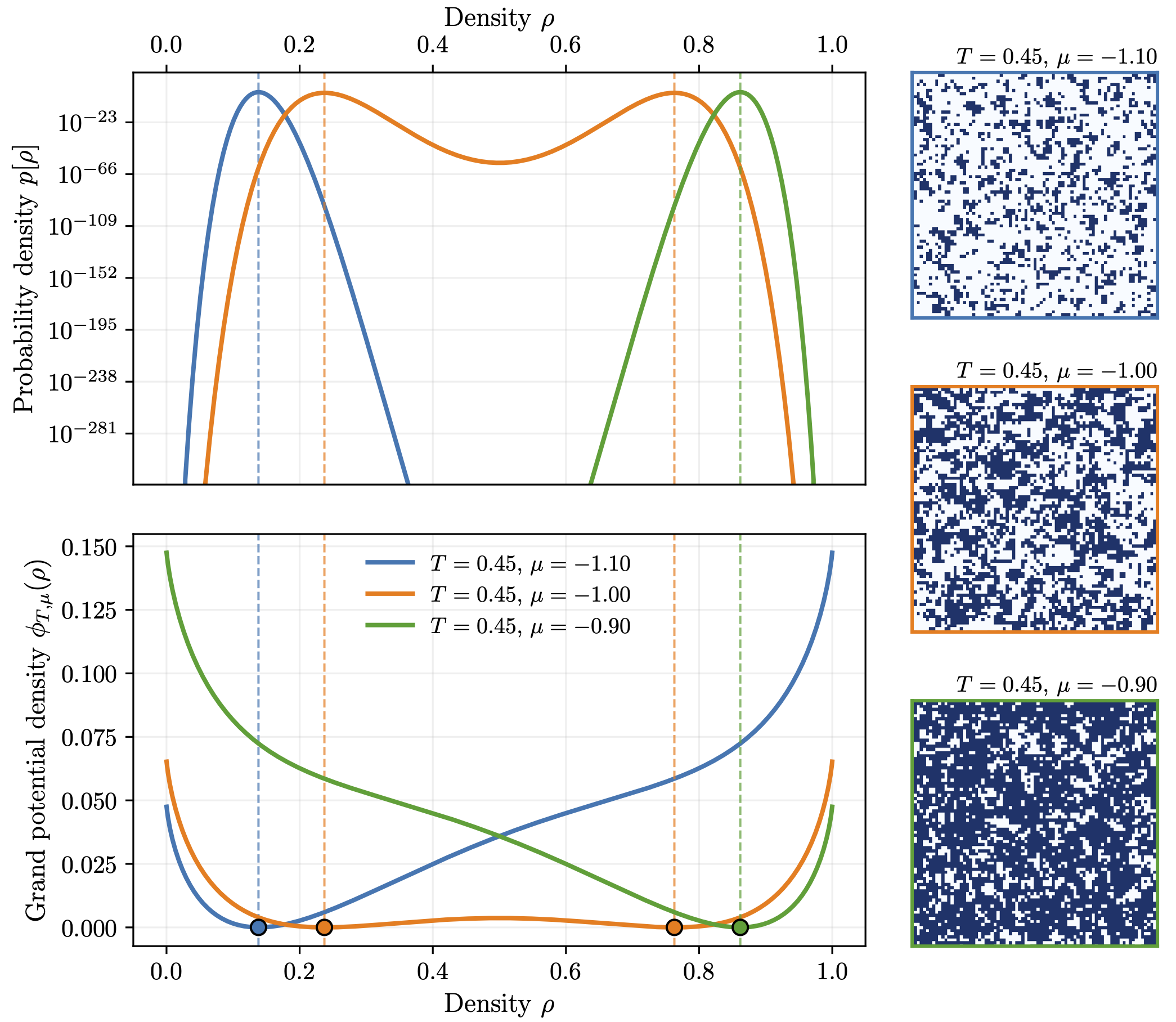

\[\mathbb{P}[\rho] \propto \exp\left(V \left[ \frac{J\rho^2 + \mu\rho}{T} - \left( \rho \ln \rho + (1-\rho)\ln(1-\rho) \right) \right] \right).\]For large systems (\(V \gg 1\)), this distribution peaks sharply at the density that minimizes the grand potential density:

\[\phi_{T,\mu}(\rho) = -J\rho^2 + T[\rho\ln\rho + (1-\rho)\ln(1-\rho)] - \mu\rho.\]

At high temperature, \(\phi_{T,\mu}(\rho)\) has a single minimum. Below \(T_c\), the landscape becomes non-convex with two minima separated by an energy barrier. At \(\mu_c = -J\), the global minimum jumps discontinuously, which is the mathematical signature of a first-order phase transition. The competition between energy and entropy is governed by the ratio \(J/T\). I built an interactive simulation tool to explore this.

Hopfield Networks and Transformers

It is no coincidence that the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Hopfield for his invention of Hopfield networks. If you take a look at the math, you can easily see that those are equivalent to the lattice gas I outlined above. A Hopfield network has binary neurons with states \(s_i \in \{-1, +1\}\) and uses the energy function

\[E = - \sum_{i \lt j} w_{ij}s_i s_j - \sum_i h_i s_i\]Comparing to the lattice gas, we can identify the following connections:

- Neuron states \(\leftrightarrow\) Occupation numbers

- Synaptic weights \(\leftrightarrow\) Couplings

- Biases \(\leftrightarrow\) Chemical potential

Similarly, a Hopfield network operates by energy minimization: neurons update such that the total energy is decreased, with local minima representing stored memories. Hopfield networks are one of the simplest neural network architectures. Training is essentially a one-shot process where connection weights are set by Hebbian learning: \(w_{ij} = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{\mu} \xi_i^{\mu} \xi_j^{\mu}\), where \(\xi^{\mu}\) are the patterns to be stored. Inference corresponds to energy minimization—presenting a noisy pattern and letting the network relax to the nearest stored memory. However, classical Hopfield networks have a limited storage capacity, typically \(\approx 0.14 N\) patterns, where \(N\) is the number of neurons. Beyond this, spurious states emerge and the network undergoes a phase transition to chaotic behavior.

Meanwhile, it turns out that there is a very straightforward way to exponentially increase the storage capacity in Hopfield networks, which in fact moves us to the attention mechanism in transformers! As shown in the amazing paper Hopfield Networks is All You Need, all that is required is replacing the quadratic energy function with an exponential interaction rule:

\[E = -\text{lse}(\beta \mathbf{X}^T \boldsymbol{\xi}) + \frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{\xi}^T\boldsymbol{\xi} + \beta^{-1}\log N + \text{const}\]where \(\text{lse}\) is the log-sum-exp function, \(\mathbf{X}\) contains stored patterns, \(\boldsymbol{\xi}\) is the query state, and \(\beta\) is inverse temperature. This gives the update rule:

\[\boldsymbol{\xi}^{\text{new}} = \mathbf{X} \cdot \text{softmax}(\beta \mathbf{X}^T \boldsymbol{\xi}).\]Attention in transformers is:

\[\text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\mathbf{V},\]which gives us the exact correspondence:

- Queries \(\mathbf{Q} \leftrightarrow\) Current state \(\boldsymbol{\xi}\)

- Keys \(\mathbf{K} \leftrightarrow\) Stored patterns \(\mathbf{X}\)

- Values \(\mathbf{V} \leftrightarrow\) Pattern content \(\mathbf{X}\)

- Temperature \(1/\sqrt{d_k} \leftrightarrow\) Inverse temperature \(\beta\)

Attention in transformers is equivalent to minimizing an energy functional in pattern space—that is, retrieving memories that best match the current query. Multi-head attention in that sense creates parallel energy landscapes, each of which specializes in different patterns. For example, one head may capture syntactic relationships, another semantics, another positional information, and so on.

With respect to the lattice gas, layer normalization also takes on an interesting role: it keeps the network in the critical regime. For low temperature, softmax becomes one-hot, and retrieval becomes rigid. For high temperature, softmax becomes uniform, and retrieval becomes random. Normalization balances exploration and exploitation. Training via backpropagation is equivalent to sculpting the energy landscape, equivalent to engineering the coupling constants in the lattice gas to achieve a specific phase behavior. Finally, grokking (sudden transitions from noise to generalization) mirrors nucleation at first-order transitions—the model explores a metastable state before suddenly transitioning to a lower-energy generalized solution.