Dendrite Networks

A cellular automaton model simulating dendritic growth with parallelized diffusion.

I use a cellular automaton (CA) model to simulate the growth of dendritic structures in terms of diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA). The simulation uses Margolus shuffling, which allows for parallelization under conservation of information and isotropic diffusion.

Cellular Automata

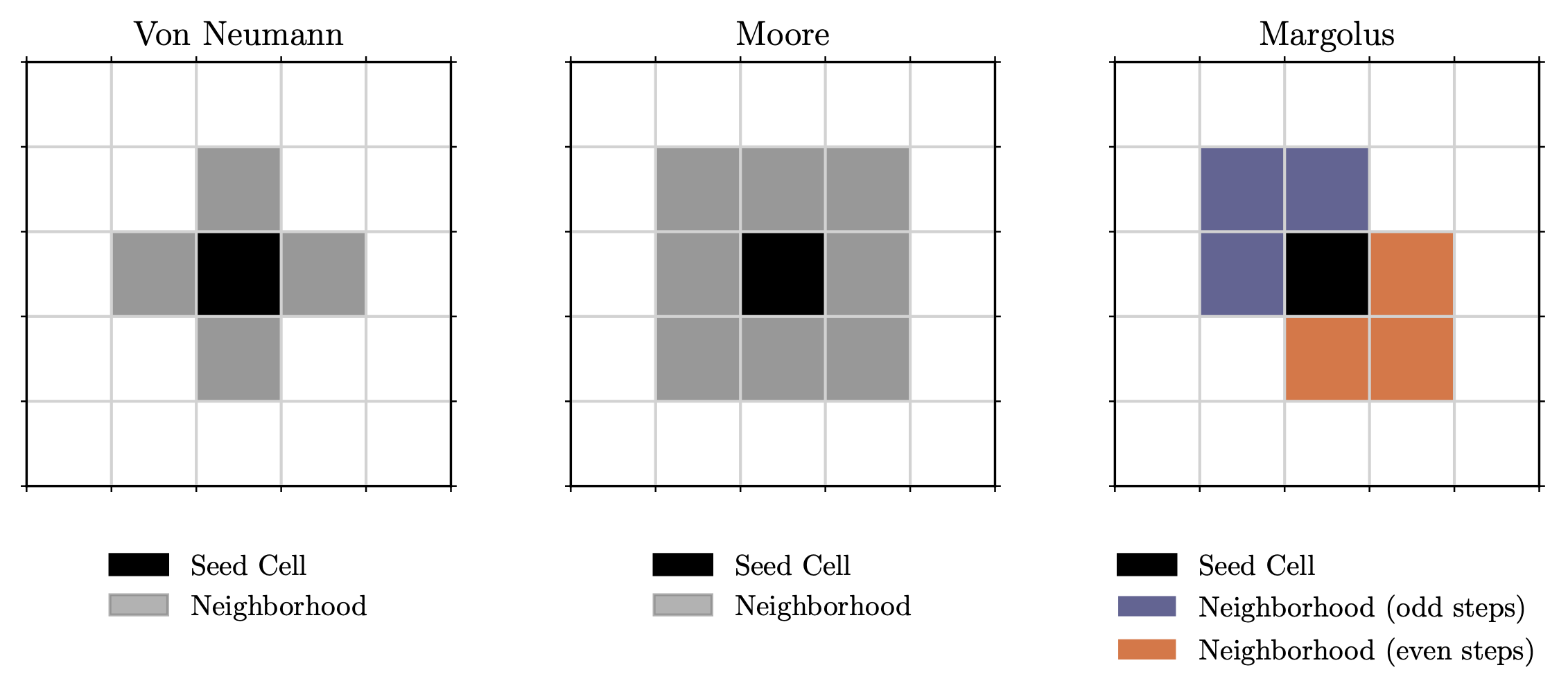

In cellular automata models, we consider a discrete grid of cells, each having a finite set of possible states. The system evolves according to fixed rules based on local cell neighborhoods. There are multiple ways of how the neighborhood can be considered, for example in terms of the Von Neumann or Moore neighborhood.

The Von Neumann neighborhood consists of a central cell and its four adjacent neighbors (up, down, left, right). The Moore neighborhood extends to the eight surrounding cells, so including the diagonals. This is also what’s used in Conway’s Game of Life. The Margolus neighborhood partitions the grid into 2×2 blocks and updates them synchronously. This partition shifts on alternating steps, allowing for reversible dynamics.

Margolus Shuffling

The Margolus shuffling algorithm follows these update rules:

1. Divide the grid into 2×2 blocks:

if time_step % 2 == 0:

Start blocks at even coordinates (0,0), (2,0), etc.

else:

Start blocks at odd coordinates (1,1), (3,1), etc.

2. For each block:

- Redistribute particles within the block according to update rules

- Conserve the total number of particles

3. Advance to the next time step

4. Repeat

The key point is that the block updates are independent from one another, which allows us to parallelize. Meanwhile, it preserves local conservation and reversibility.

To model aggregation, we initialize the grid with a (fixed) seed in the center and randomly distributed (free) particles in a given density. The update rules are quite simple:

For each free particle:

- If any neighbor is part of aggregate:

Join particle to aggregate

- Else:

Remain free for Margolus shuffling

We here consider only neighbors in the Von Neumann neighborhood for sticking. Moving to larger numbers of particles, we get fractals of high complexity.

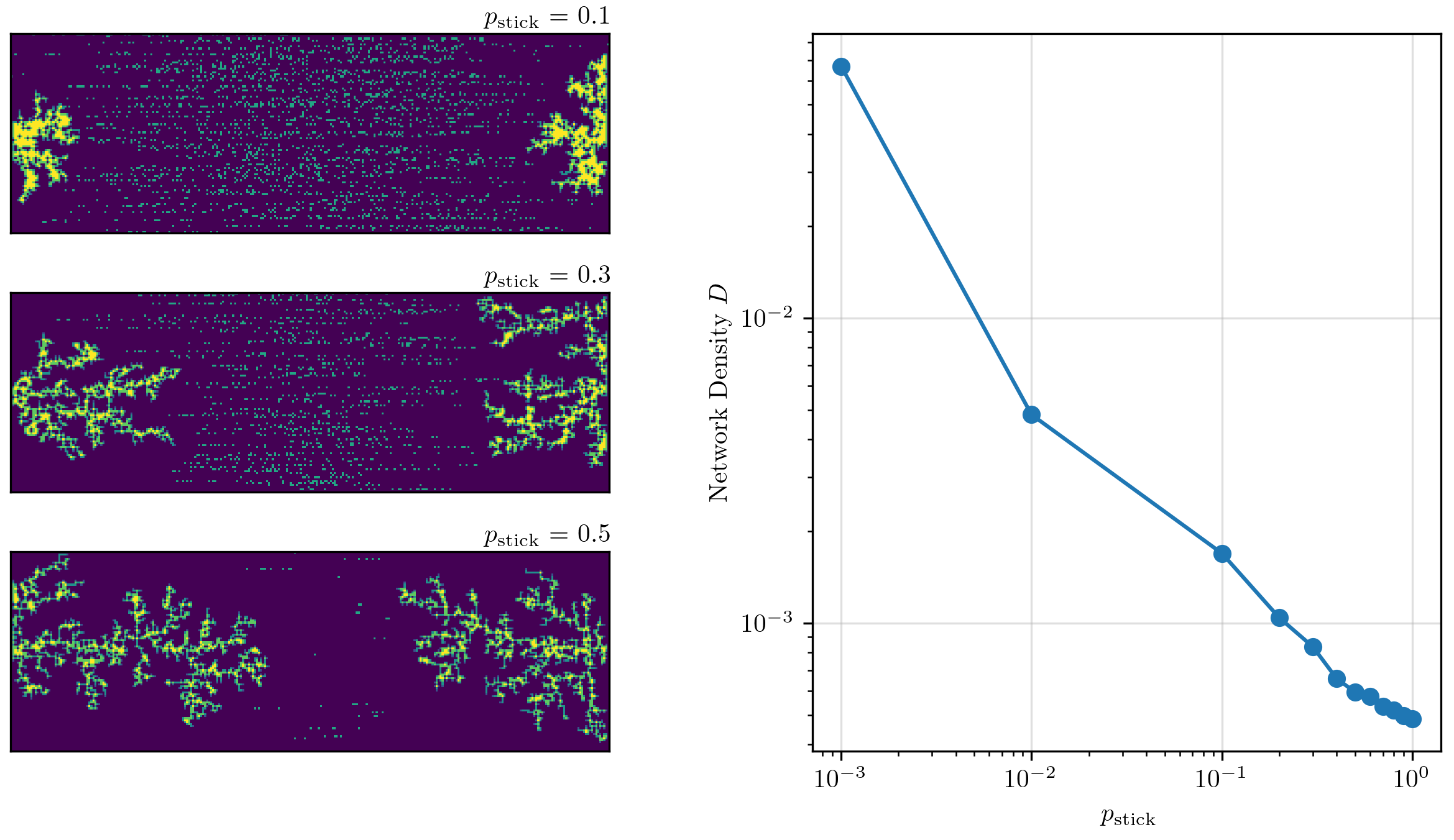

Probabilistic Aggregation

We introduce a sticking probability $p_{\text{stick}}$. For each free particle $i$ that is adjacent to a fixed cell, we sample it with

\[p_{\text{stick}} > U_i \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1).\]Diffusion under Bias

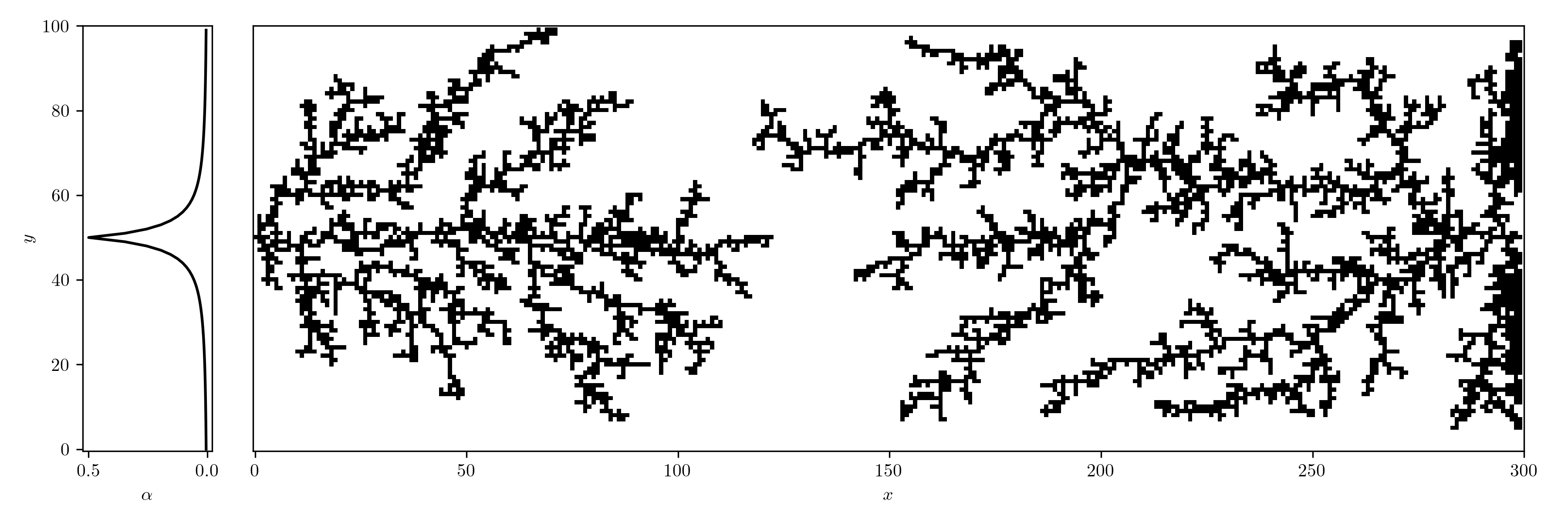

We also introduce a bias into the shuffling algorithm. Within each 2x2 block, we consider a horizontal and a vertical pair, corresponding to the left/right and top/bottom cells. Transitions in each pair are biased by a field $\mathbf{F} = (F_x, F_y)$ with strength $\alpha$. For $F_x > 0$, the probability of a move to the right is

\[p_{\text{right}} \;=\; \frac{ e^{\,\alpha \, F_x} }{ e^{\,\alpha \, F_x} \;+\; 1 }.\]For a move to the left, it is

\[p_{\text{left}} = 1- p_{\text{right}} \;=\; \frac{ e^{-\alpha \, F_x} }{ e^{-\alpha \, F_x} \;+\; 1 }.\]Vertical moves would follow the same pattern using $F_y$.

We can now introduce an oscillating bias and consider the case with two seeds. We let the field decay in the vertical direction by $r^{-2}$ (Coulomb).

Network Analysis

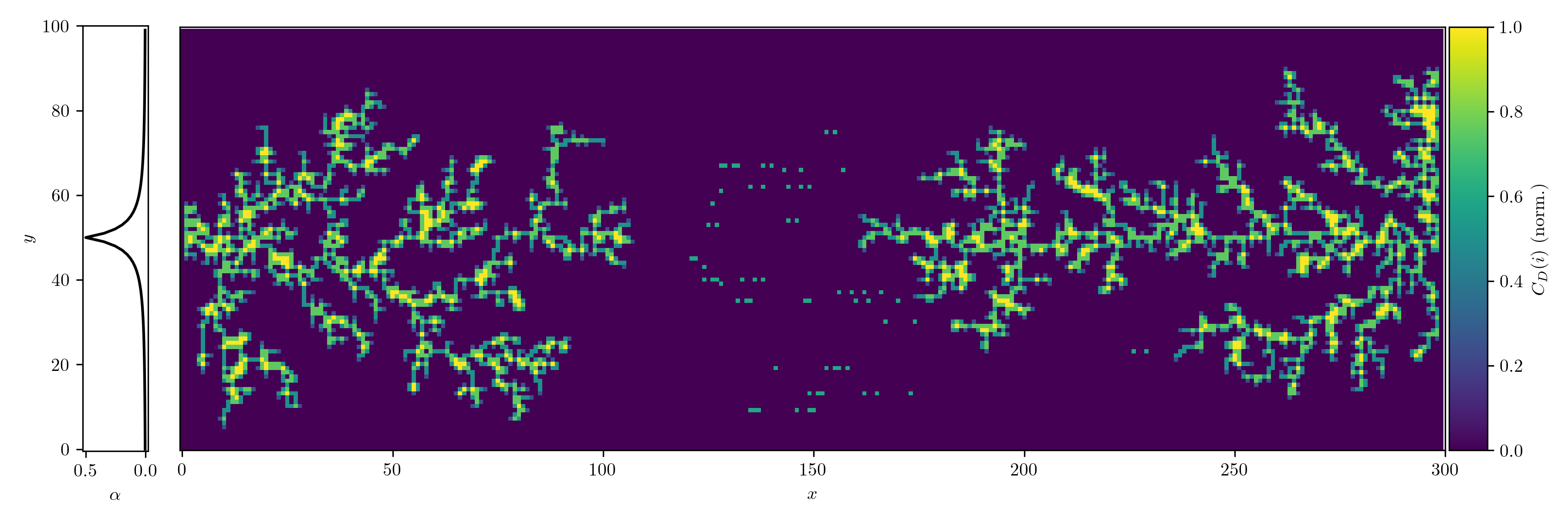

We can treat the dendrite structures as graphs and analyze them using network theory: occupied cells are considered as nodes, which are connected by edges. We can then use the degree centrality metric to measure how connected each node is within the network. For a node $v$, the degree centrality $C_D(v)$ is defined as:

\[C_D(v) = \frac{d(v)}{n-1}\]where $d(v)$ is the number of edges connected to node $v$, and $n$ is the total number of nodes in the network. Since we use the von Neumann neighborhood, each node can have a maximum degree of 4.

We can also calculate the network density for the total graph. The density $D$ is defined as the ratio of the number of actual edges $\lvert E \rvert$ (the cardinality of the set $E$) in the network to the maximum possible number of edges. For an undirected graph without self-loops, the maximum number of edges is

\[|E|_\text{max} = \frac{n(n-1)}{2},\]where $n$ is the total number of nodes. The network density is therefore

\[D = \frac{2|E|}{n(n-1)}.\]

Relevance

This DLA based on CA mimics a plethora of processes in nature. Just to name a few examples:

- Dendritic growth in biological neural networks

- Percolation growth in condensed matter

- Dielectric field breakdown in insulators

- Electropolymerization

It certainly has some parallels with the late works of Alan Turing